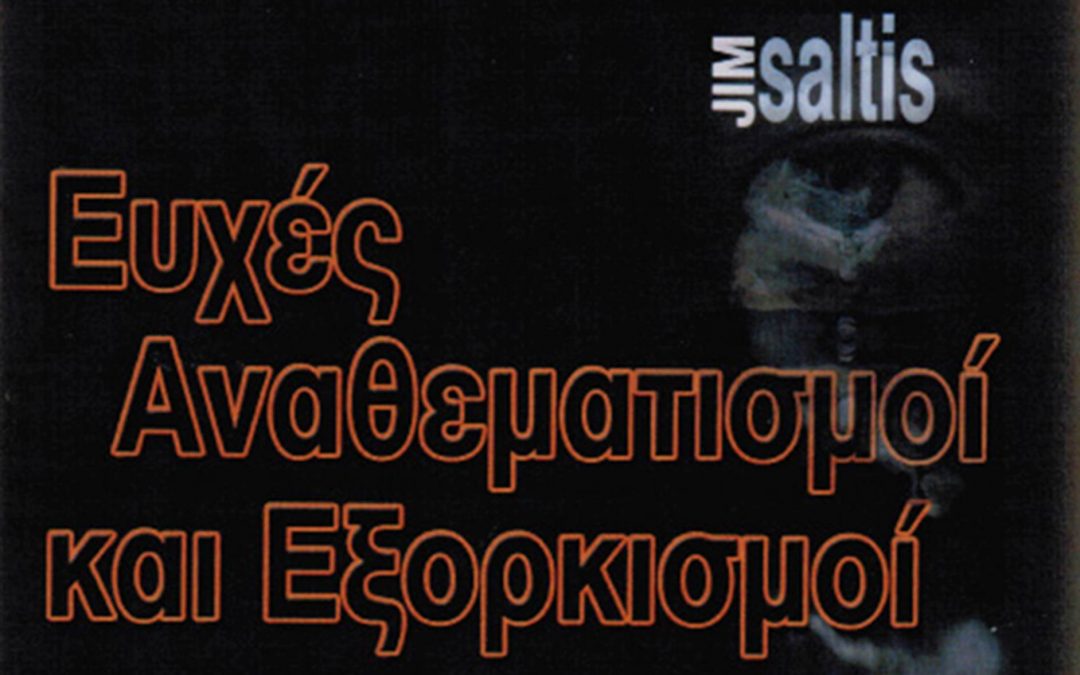

E.E.A.M.A. in collaboration with the Greek-Australian Cultural League invite you to Jim Saltis’ book launch of “Blessings, Curses and Exorcisms, on Sunday 31st August, 2014, 3.00pm, at the Stars International reception centre, 1C Bell Street, Preston.

The book will be presented by the well known and acclaimed Alexandrian poet and artist, Nikos Nomikos. The launch will be hosted by the GACL’s Secretary, Kathy Aronis

A few words about the book from the author:

“Alexandria was the city where I was born, grew up and finally left in January 1949, without hatred or wickedness. One night, after my divorce in 1988, when sleep was minimal and agitated I decided to put some exploitation to my insomnia and started writing my first book which I titled as “Mrs Stamata”.

Many years have logged since then, before finally I seriously went back to the skeletal book to turn it into a novel. The book includes my own empirical experiences and also fantasies that dwelled between my perpetually moving brain and my invisible soul.

Many years have logged since then, before finally I seriously went back to the skeletal book to turn it into a novel. The book includes my own empirical experiences and also fantasies that dwelled between my perpetually moving brain and my invisible soul.

The people you will encounter in this novel have lived their sojourn on this planet. Even the prodigal and very beautiful Flora (Madeline) who was lucky to experience the true live from Milton. I gave Sofia a happy ending after the untimely departure of her husband Alecos. Stamata died a long time ago but she carries on living as ghost at the Greek section of the cemetery at Chatby while waiting for the Second Coming of Jesus.

The book takes place in the Alexandrine district and it includes words from the different languages that the Europeans used including of course the Arabic. These days all of us who were born in the magical city of Alexandria, live dispersed on the hospitable planet. We have travelled on new seas and flew over skies and countries we have learned from our Geography books. We have comfortably settled and now enjoy leisurely existences in our old age. Yet are always grateful that we were born in Egypt.”

Αll welcome refreshments will be provided at the end of the proceedings

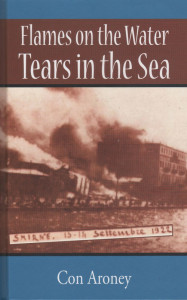

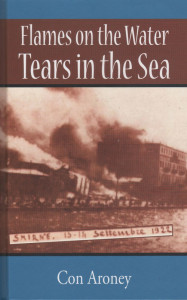

The GACL in collaboration with the Pontian Community of Melbourne and Victoria launched Dr Con Aroney’s book Flames in the Water, Tears in the Sea on Saturday 17th May, at the Pontian Community building in Brunswick.

The book was the result of his five year labour of love, as he said, “…it had to be done one day”.

The book was the result of his five year labour of love, as he said, “…it had to be done one day”.

A powerful historical novel about one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century, the destruction of a prosperous Mediterranean city, the massacre of hundreds of thousands of its multicultural inhabitants and the displacement of millions more. The book is based on the involvement of the author’s family in the actual events of the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922.

It was Dr Aroney’s maternal grandmother Eugenia, who would describe in detail what had happened to her family in Asia Minor, telling stories of their losses and their salvation.

Con Aroney’s book is a reconstruction of the historical event that took place in Smyrna-the melting pot of different ethnic groups- told through three interwoven stories, those of the author’s maternal grandparents , the Girdie and the Caristinos families and an unknown hero, Asa Kent Jennings.

In her speech to launch the book, the President of the GACL, Cathy Alexopoulos said, “We are honoured to have with us Dr Con Aroney, such an important occasion and feel very privileged to have in our midst a celebrated academic, a scientist, a researcher, in more ways than one, a man who did not forget his roots and found the time to pay tribute to his ancestors by writing their story thus their legacy lives on with all of us.”

The book Flames in the Water, Tears in the Sea is available through the publisher at www.copyright.net.au

On Sunday 17th May at 3.00 pm., Dr Con Aroney will launch his book Flames in the Water Tears in the Sea, a powerful historical novel about one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century, at the Pontian Community of Melbourne, 345 Victoria St., Brunswick.

Dr Con Aroney’s book

The book will be presented by academic and writer Konstandina Dounis and journalist Claire Gazis.

Ian Matthews in his review in the Order of Australia Magazine The Order (No 35, Autumn 2014) he writes: “Terrible reality in facts and fiction Flames on the Water, Tears in the Sea by Con Aroney AM, Published by CopyRight Publishing, Brisbane RRP $27.50. It is a curious fact that a novel can often convey atmosphere, emotion and veracity about historic events better than an academic record or forensic investigation.

When Thomas Keneally AO wrote Schindler’s Ark as a prize-winning work of fiction, it was based on copious testimony. He observed, “To use the texture and devices of a novel to tell a true story is a course which has frequently been followed in modern writing.

It is the one I have chosen to follow here, both because the craft of the novelist is the only craft to which I can lay claim and because the novel’s techniques seem suited for a character of such ambiguity and magnitude as Oskar [Schindler].”

Con Aroney has woven a novel around the almost forgotten facts of the rescue of about 300,000 Greek women, children and aged refugees from Smyrna, now Izmir, Turkey, after an onslaught by Turkish forces in 1922.

Drawing on his family’s history, Professor Aroney tells the grim story of yet another of the 20th century’s massacres — but one that could have been infinitely worse but for the work of an American YMCA worker, Asa Jennings. He negotiated with Kemal Ataturk for time to have the Greek refugees taken to the relative safety of Greek islands.

He then bargained or blackmailed the Greek government of the day to supply ships to take the homeless thousands from the port of Smyrna. Both Greece and Turkey regarded Jennings as a humanitarian hero and, incredibly, at one stage he represented both countries. Con Aroney has written a riveting diary of tragic events from his family’s point of view.

He explains, “All major events including the battles leading up to the destruction of Smyrna, the great fire, the evacuation and aftermath are closely based on the actual historic events, although the specific military and social actions of some of the characters are in part fictionalised.”

The book follows an easy-to-read diary format with many short chapters and includes helpful maps and dates. It is a sobering commentary on civilised society that in our own lifetime we have become so inured to the litany of horrors of the Holocaust, the slaughter in Rwanda, the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, the massacre at My Lai that the 1922 Catastrophe at Smyrna has slipped our notice. Con Aroney’s novel reminds us never to forget.”

Litsa’s book, titled “Some Truths” is autobiographical and divided into two parts, the first covers the period from when Litsa was young-during and after the second world war and the second part refers to her migration to Australia in 1956 till today.

This is Litsa’s seventh book and true to her style full of humanity, optimism and love for the underdog, she exposes without any reservations some truths that have struck a chord in her entire being as been unjust, unforgiveable and illogical. Her accounts are spontaneous and testify her search for a harmonious and equitable world. Her memory is remarkable in its clarity and coherence and she retraces events have left a mark in her life, events that have been painful and life changing, such as the incident with the old man, the “so-called” protector who made inappropriate and improper advances to her when she was a mere 8 year old child. The tortured and tormented budding youth of the war years was exposed to all sorts of exploitation, ill-treatment and abuse. The constant misery of living with only the clothes on your back and going to sleep hungry every night, not to mention the need to ask for charitable handouts to get through the day, are certainly character building and significant moments in these impressionable years. Everyone in the family had a role to play and he/she had no option but to obey the rules in order to survive. At the same time Litsa describes the wonderful and carefree times she and all her friends and relatives spent together playing games, doing chores, visiting friends-activities that today’s children would not have the freedom or be allowed to play. These children were certainly never “bored”.

Litsa makes reference to her large family’s struggle to survive in several of the short stories -she cites many instances of the hardships endured during and after the war years, such as the time when she was 8 and her older brother was 12 and they were temporarily fostered out to a distant relative whose handling of the children was far from humane and benevolent- but they endured it for a full stomach…

Litsa migrated to Australia in 1956 through the free passage available at that time from an organisation called DEME (an inter-governmental agreement) as long as you became a factory or rural worker of some sort in the growing industrialisation of Australia at that time.

Her life in Australia was by no means what she had dreamt or envisaged. Her initial experience with her “fiancé” was so distressful and distasteful that she began to live a new nightmare, an unforgettable experience that led her to make many concessions in her life.

Despite her protests Litsa finally agreed to an arranged marriage by her uncle to someone she did know or cared for. The trap was laid but where could she turn? She had no family, no support, no money, no real work, her wings were clipped and she could not fly, there was no escape. A wounded, lonely bird shaking with fear in the stormy ocean of insecurity and uncertainty.

Litsa raises a very important ethical issue-how is it that while under the protection of the of the family the female had to be obedient and adhere to the strict moral code of male/female relationships and yet once she stepped her foot away from that paternal threshold, she was exposed to unknown and unforeseen circumstances and left to her own devices to deal with them? “Out of sight, out of mind.”

Not only did the newcomers have to learn to adapt to the new life in a different geographical environment with an unfamiliar culture, a foreign language, unknown customs and social norms, but they also had to adjust to married life, in many cases in creating a home with an unknown person, rearing a family, creating friendship groups, finding work and the list is endless. They were prepared to go to any extent to secure “a deposito” towards the purchase of their own home, to get out of the rut of poverty and misery that they had endured all those years in their motherland.

Litsa gives many instances of the comradedary that developed with new friends, the time when she and her girl-friend wanted to make a traditional sweet from grapes and they left the sweet cooking on the fire while they went to the shop to get extra ingredients, only to return home (the rented home) to find that the pot had overflowed and the syrup was everywhere. The fear of being found out by their strict landlord is another reminder of the difficulties that confronted the newcomers.

She also describes how she gave birth to their first child- almost on the tram while going to work. This is reminiscent of the stories I have been told in Greece of the women working in the fields, giving birth and then continuing to harvest or water the land.

While reading the book at different parts you get the sense that this generation was the sacrificial lamb destined to be “slaughtered” in order to wipe clean all the impurities of the old order as well as assist in the social and industrial development of “Terra Australis”.

Wherever you live, life has its highs and lows and the migrant story is typical of this- Litsa accounts several tragic incidents that stamped the rest of her life, such as the untimely and tragic death of her oldest grandson, George, in a motor car accident. Also the unfortunate death of a very young child belonging to a friendly family who was the victim of the migrant’s struggle to improve their lot in life- the child accidently spilt a pot of boiling water over its body and subsequently died from its wounds.

Despite the adversity encountered by the first generation Litsa does not always paint a picture of “doom and gloom”, she manages to make reference to some lighter moments, such as when her husband, George, had painted the kitchen chairs red with left over paint. On her sister’s wedding day, her brother-in-law who was wearing a white shirt sat on one of the red chairs and needless to say that it became a shade of pink very soon.

Finally, Litsa’s kind-hearted and compassionate nature does not forget the hardships faced by the children of the migrants- their parents almost compulsive need to “follow the dollar”, their lack of communication skills, their absence from home, their inability to participate in the child’s school environment, to mention a few of the adverse situations their children had to overcome.

She pays tribute to them and says-“…my pitiful, tormented children, you too have suffered and tasted the bitterness and problems of migration.”

This book is a testament of the migrant women’s voice, the forced mass migration imposed on the thousands of men and women who had lived not only the trauma of the war years but also the depravation of the civil war that followed. Poverty and destitution filled their existence and their only solution was to find salvation in foreign shores.

Litsa describes her trials and tribulations with an authentic, raw and truthful manner, she does not hold back and is not ashamed of what she had experienced. In fact she is proud of what she accomplished, her family, her children, her grandchildren, her circle of friends and her status in society.

Congratulations Litsa for another milestone in your writing path.

– Cathy Alexopoulos

On Sunday 8th September, at 3.00 pm, the GACL, the Greek Orthodox Community of Melbourne and Victoria and the Hellenic Writers Association of Australia, will launch Kostas Kalymnios three new poetry collections Anisixasmos, Plektani and Kelifospastis at the Panarcadian Association of Victoria “O Kolokotronis” hall, 2nd floor, 570 Victoria St., North Melbourne.

Dr Vrasidas Karalis of Sydney University will be launching the books and M.C. will be Dimitris Tsahouridis.

This is a well-inspired and pleasingly narrated novel unfolded in 17 Chapters; most of the set narrating stages are being build up in the war and tragedy-stricken Greece (ten chapters), two aboard Italian steamship Aurelia and five in Australia. The main narration of the novel, 15 Chapters, is being unfolded within a time of approximately 14 years (1940-1952). The author uses two main narrative approaches, one via the mind and conscience/sub-conscience of her protagonist, Tasia, and one direct as the compiling author.

The overall narration is characterized/ by the sharp contrasts in emphasis and perceptions defining the Australian socio-economic and cultural landscape, between the harsh and callous pioneering years of the protagonists in Terra Australis depicted in the three last chapters of the novel and the warm-heartened and gentle years of integration, maturity and citizenship reached by the protagonist fifty years later. The narration of the tragic events in Greece through continuous warfare, famine, political and socio-economic instability are portrayed vividly and truthfully. Gessa-Liveriadis portrays in a charismatic and earnest way the turbulent, violent and chaotic modern history of Greece through the innocent eyes of a child, depicting the turmoil of the German Occupation (1941-1945), the Greek Civil war (1946-1949) shading light and devoting certain portions of her native in the national and natural disasters that stroke Greece in the 20th century.

The popular description of her characters in the villages and the ethnographic and folklore portrayal of her daily characters, their dialogues and daily practices are very vivid and colorful to the extent that every reader could identify for himself/herself certain aspects of their features and their recitations. The individual personalities outlined in her novel are very real and their stories and characters are being unfolded in a realistic and vigorous way. Gessa-Liveriadis should be praised for navigating through these difficult years for Greece in a way that is broadly speaking impartial. Naturally certain historical events are not presented in their accurate perspective; yet, this is literature and in poetry and literature the creator could establish even the impossible as a reality; after all Homer made Penelope to give a birth at her 90th year of age!

Her protagonist, Tasia, is a romantic, passionate, idealistic and sometimes naïve person who is stricken by an ill-fated and to a certain extent histrionic life, at least until the end of her first wedding; elements of Greek drama are shed to almost all of her casting list; Gessa-Liveriadis narrative modus operandi remains the ‘unexpected’, the bolt from the blue, from the very first page of her novel to the last word. She wishes to take her readers by surprise, to keep them astonished by the heaviness awful destructions and human atrocities; her objective is to describe the climax of dreadful trials, to upgrade the drama of the events or to express the extreme and self-sacrificing attitudes or the grotesque and inhuman mode of behavior of her protagonists. The author prefers the crescendo in her style of writing. Some readers may question the volume of blood consumed in the novel or the quantity of deaths, the amount of perishing opportunities, the level of human waste, the size of tragedy and the amount of drama; however, equally so, tragic and immensely catastrophic and heart-rending has been the 20th century Greek history through the eyes of deprived and destitute citizens, impoverished refugees and victims of terrible religious persecutions, appalling ethnic cleansings and heartbreaking catastrophes.

Gessa-Liveriadis’ novel is a very valuable literary creation; its contribution is significant for the understanding of the Greek way of life, the ethos, the social order and characteristics of the Greek villages and regional urban centers like Ptolemais; her description of Greek institutional life, the Church, the police and the people with authority are real and deserve praise as indeed level-headed and genuine are her descriptions of the popular village characters, especially those in the local Kaphenion and the ladies of speculation in the villages; the portrayal of the multi-lingual and multi-cultural populations in Macedonia, the existing divisions between indigenous and refugees in her village and in Ptolemais; particularly important are her inter-communal descriptions in Greece and her generous intra-family relations. It is also rather curious from the reader’s perspective that although Tasia’s relation with her parents receive due attention, her brother, Kostas, is being mentioned with a passing reference manner, only in three occasions. Gessa-Liveriadis uses or eliminates her protagonists always having as the objective to surprise her readers. Overall, her narration is a useful tool for anthropologists and ethnographers studying 20th century Greek social life.

The origins of Greek migration and settlement and the contributing causes that triggered the huge migration of 270.000 Greeks and Cypriots in Australia are primarily portrays in this novel during the period 1952-1975. Gessa-Liveriadis outlines the procedures for application, the terms of selection and the way of life of the incoming immigrants in their ships to Australia . She also gives a rather short and feeble description of the immigrant way of life in the inner suburban areas and in particular that of Richmond, where communal life was necessitated. The real and the imaginary, the factual and the false in the mental process, the rational and the irrational are all intermingled presenting the outcomes of a life in turmoil. This becomes particularly important and true when the reader, after concluding the reading of the last Chapter, could read again the very first one, to experience the outmost tranquility, the Catharsis of the Ancient Greek drama.

Professor Dr. Anastasios M. Tamis

School of Arts and Science

The University of Notre Dame Australia

21 May 2011

Many years have logged since then, before finally I seriously went back to the skeletal book to turn it into a novel. The book includes my own empirical experiences and also fantasies that dwelled between my perpetually moving brain and my invisible soul.

Many years have logged since then, before finally I seriously went back to the skeletal book to turn it into a novel. The book includes my own empirical experiences and also fantasies that dwelled between my perpetually moving brain and my invisible soul.